Bringing hope to a place no one should have to call home

Sam Cleary, a water and sanitation engineer and Red Cross aid worker, shares this story of life in the refugee camps on the Bangladesh-Myanmar border.

Perspiration pours from Mosi’s brow in the searing heat as a new water borehole is dug deep in the heart of the Bangladesh camps. He looks up as the machinery shudders and we laugh. A sense of humour is critical in a place where so many people have been through so much pain.

This week marks 18 months since villages burnt to the ground amid violence in Rakhine, Myanmar. Today there are times when the pain here is still palpable. Too many eyes are still glazed with fear.

We’re drilling hundreds of metres deep below the surface of the camps that border Myanmar. Throughout this mega-camp, carved into what were once forested hills, there are now over 12,000 bore holes dug into the hillsides. They ensure people have enough water for drinking, washing and cooking. There are so many holes the camp resembles Swiss cheese.

Mosi, escaped the violence with his wife, seven children, three brothers and two sisters, plus their extended families. Their story is like so many living in these camps.

We’re drilling hundreds of metres deep below the surface of the camps that border Myanmar. Throughout this mega-camp, carved into what were once forested hills, there are now over 12,000 bore holes dug into the hillsides. They ensure people have enough water for drinking, washing and cooking. There are so many holes the camp resembles Swiss cheese.

Mosi, escaped the violence with his wife, seven children, three brothers and two sisters, plus their extended families. Their story is like so many living in these camps.

When their village burnt to the ground, they hid in the jungle for eight days with next to no food. They slept in the rain alongside mosquitoes, spiders and snakes.

Their family joined the mass exodus, a surge of humanity spilling across the border from Myanmar to Bangladesh. It is one of the largest ever movements of people in our region. Mosi says everyone was just looking for somewhere safe.

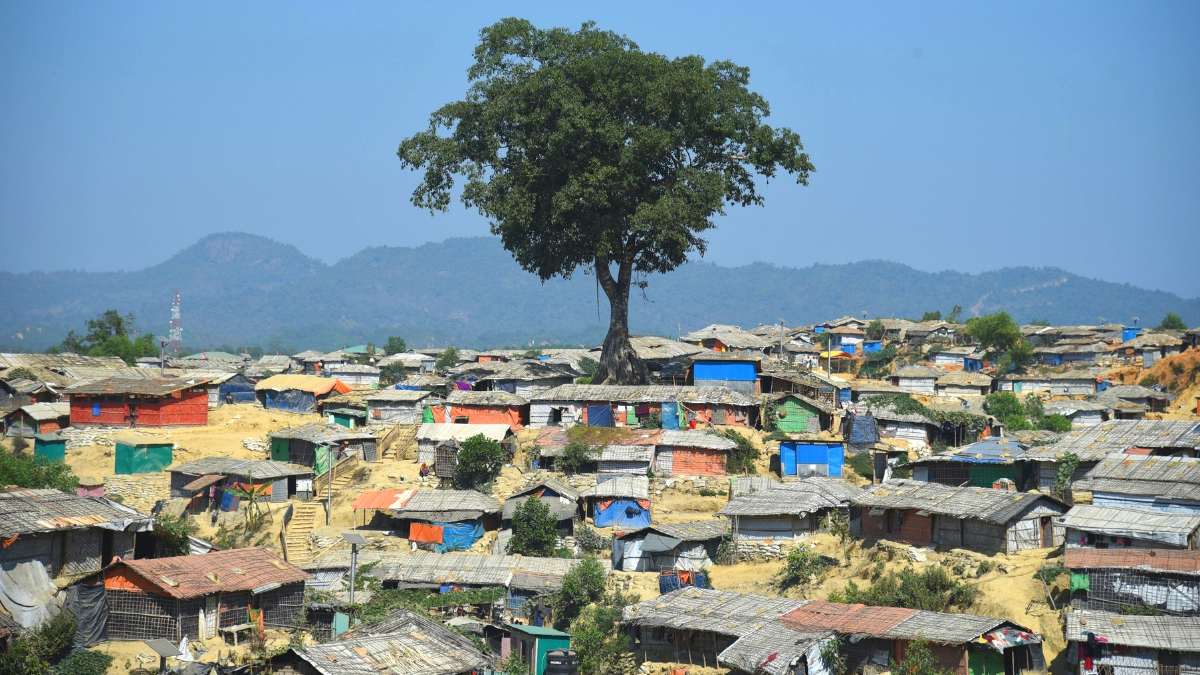

Here in the camps, there is some safety. Hundreds of thousands of people live in flimsy structures of bamboo and plastic held together by string. Everyone is making the best of their new homes. I see personal flourishes everywhere; bright sarongs mark a front door, bamboo weaved for a window, shells line a doorway. It strikes me time and again that no one deserves to live like this.

This is one of the most densely populated places on earth. Approximately 75,000 people are crammed in to every square kilometre.

Here in the camps, there is some safety. Hundreds of thousands of people live in flimsy structures of bamboo and plastic held together by string. Everyone is making the best of their new homes. I see personal flourishes everywhere; bright sarongs mark a front door, bamboo weaved for a window, shells line a doorway. It strikes me time and again that no one deserves to live like this.

This is one of the most densely populated places on earth. Approximately 75,000 people are crammed in to every square kilometre.

In the first days I arrived in the camps, one year ago, I was blown away by the speed of change. Frantic building everywhere; new schools and learning centres, thousands of hillside footpaths etched and winding through the labyrinth of homes. These are resilient people taking control of their lives and making the most of the little they have.

I was awestruck by how resourceful people were here. New businesses sprang up all over the camps. People erected little shops to earn an income selling everything from watermelons to fried samosas and phone chargers.

I was awestruck by how resourceful people were here. New businesses sprang up all over the camps. People erected little shops to earn an income selling everything from watermelons to fried samosas and phone chargers.

Every day, a new challenge. During the monsoon season we trudged through thick mud to find new locations for boreholes. We return days later only to find a family building a new shelter on the site we had identified. A mad scramble followed to find another suitable location to dig.

It’s difficult and frustrating to change our plans. Then again, who am I to complain when parents are only trying to find a suitable place to raise their families among the dirt and debris they now call home.

It’s difficult and frustrating to change our plans. Then again, who am I to complain when parents are only trying to find a suitable place to raise their families among the dirt and debris they now call home.

I remember the time I arrived at a large tarpaulin-lined hut for a training session with community leaders about how to treat drinking water with chlorine tablets. Idris, one of the leaders, explained lots of people were keen to take part but the training had to be postponed because the collection time for the monthly food parcels had changed.

I made the trek with Idris on narrow, slippery paths, past festering ponds being converted to vegetable gardens, to let the community leaders know the rescheduled time for the training.

I made the trek with Idris on narrow, slippery paths, past festering ponds being converted to vegetable gardens, to let the community leaders know the rescheduled time for the training.

When I arrived, I saw hundreds of people standing in lines, like the herding of sheep into fenced pens. They stood in fierce sunshine with looks of helplessness on their faces. I won’t forget this any time soon.

From day one, one of my biggest tasks was clear: thousands of boreholes means a lot of maintenance. Some holes drilled just a year ago have stopped working because of missing parts such as a pump handle, a bolt or a rubber washer. Small parts can mean the difference between clean water and a disease like diarrhoea ripping through a section of the camp like wildfire. Diarrhoea kills children here.

After arriving I noticed the quality of some boreholes was dubious. I knew we had to keep the drilling contractors accountable to ensure high quality construction. Mosi and I trained a team of community supervisors who oversaw the drilling process.

These supervisors would be the ones using the borehole for potentially years to come. It was in their best interest that the work was of high quality.

The torrential rains and winds from the yearly cyclone and monsoon seasons are imminent. Last July we got more rain in one week than my hometown of Perth gets annually. Every day, we’re shoring up more homes, foundations and infrastructure. We are still constructing new toilets, but the big focus now is making sure the waste pits are emptied frequently so the toilets do not overflow. Preventing disease is a never-ending battle.

These supervisors would be the ones using the borehole for potentially years to come. It was in their best interest that the work was of high quality.

The torrential rains and winds from the yearly cyclone and monsoon seasons are imminent. Last July we got more rain in one week than my hometown of Perth gets annually. Every day, we’re shoring up more homes, foundations and infrastructure. We are still constructing new toilets, but the big focus now is making sure the waste pits are emptied frequently so the toilets do not overflow. Preventing disease is a never-ending battle.

Trudging home with Mosi after a hard day’s work, the sun sets on the camp and I’m struck by its surreal and frightening beauty. Mosi and his friends say they want to live with some sort of dignity and safety.

He says their children want to learn, go to school, laugh and play. They tell me one day, they hope to return home to Myanmar. They fear without safety guaranteed, this won’t be any time soon.

Charity donations of $2 or more to Australian Red Cross may be tax deductible in Australia. Site protected by Google Invisible reCAPTCHA. © Australian Red Cross 2025. ABN 50 169 561 394