HUMANITECH

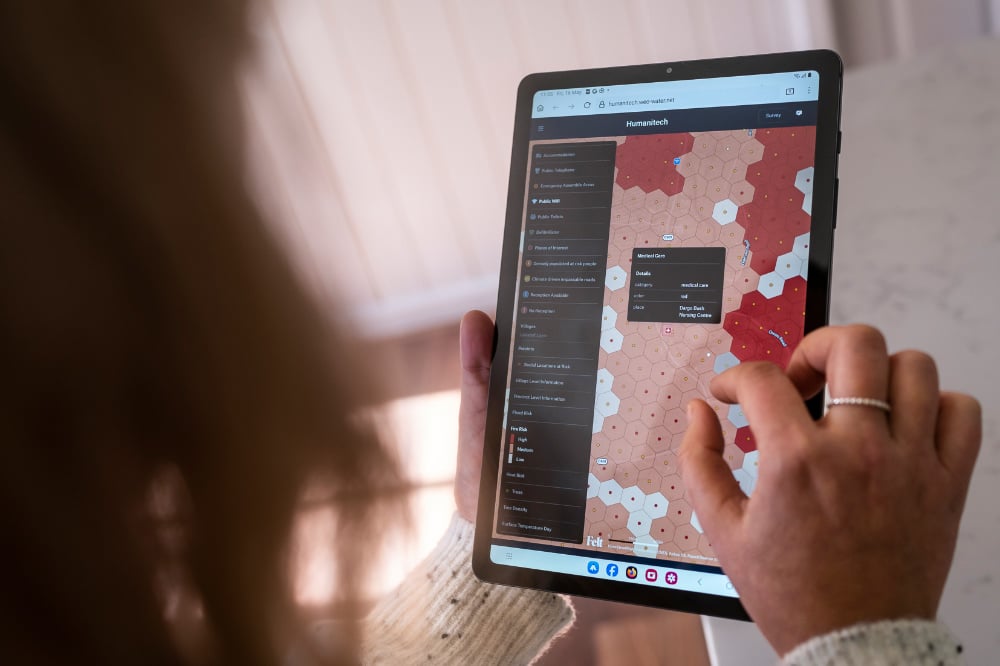

In a remote Alpine town in Victoria called Dargo — population 105 — we’ve been piloting something deceptively simple: a map.

At Humanitech, we don’t just test whether a tech solution works — we explore how it’s built, who it’s built with and whether it earns trust where it matters most. This pilot was no exception.

From the outset, the goal wasn’t to drop in a ready-made platform. It was to shape something useful and usable — with the community, not just for them. Along the way, the pilot raised deeper questions that sit at the heart of our work:

Here’s what we learnt.

The Dargo pilot emerged through the QBE AcceliCITY Humanitarian Challenge — a partnership between Australian Red Cross, QBE Foundation and Leading Cities, and was made possible with funding support from The Coca-Cola Foundation.

WEO, a satellite and AI mapping company, won the 2024 Challenge with a hyperlocal platform combining satellite data, AI and local insights to help communities understand and adapt to climate risks.

Dargo was chosen as the pilot site not just because of its repeat exposure to fires, floods and storms — but because of the way the community had already shown up for each other. Through the RediCommunities program, locals had been leading their own recovery — mapping risks, strengthening connections and planning for what might come next. Their practicality, proactivity and openness meant when the idea of trialling a new climate tech tool was raised, they didn’t just say yes — they leaned in, ready to shape it to fit their place.

This pilot wasn’t about rolling out a platform. It was about reshaping it, together.

The pilot began not with tech, but with the real-world challenges communities like Dargo face.

Questions emerged through conversations and workshops, centred on connection, preparedness and care:

Over 45 members of the Dargo community joined co-design workshops throughout the pilot, and around 80 community members in total have been involved across events and engagements linked to the project. They shared local priorities — roads that flood early, areas where visitors congregate, communications black spots and key assets like community-owned generators or Wi-Fi spots.

Bringing together different perspectives revealed where the platform needed to evolve. Some of the original design elements — like the language, risk categories or interface — didn’t quite align with how locals navigated and made decisions.

The pilot team saw these moments as opportunities to strengthen the tool — together. WEO listened and adapted. Categories were simplified. Labels changed. The platform’s navigation was redesigned to make it more intuitive. New layers were added — not just fire and flood maps, but assembly points, healthcare locations and socially important landmarks.

The result was a tool shaped by the community — one that felt practical, grounded and locally relevant.

The pilot didn’t just deliver a better map. It built something harder to quantify: confidence.

Residents saw that their knowledge mattered. They saw the platform shift in response to their feedback. That created a sense of ownership — reinforced by training local community champions who now act as trusted go-to’s for the platform.

This was co-design at its best: not a one-off workshop, but an ongoing process that ceded control, embedded trust and built local capability.

In fact, one of the biggest surprises was how fast the community moved. While the tech team expected co-design to slow things down, it was often the development timeline that had to catch up to the clarity and momentum coming from locals.

Today, the Dargo community use the platform to:

The tool has become part of the town’s planning fabric. It’s used in community meetings and disaster preparedness sessions. And because it reflects what matters locally, it’s trusted.

That’s not to say the work is done. Some requests — like real-time road closures, tracking aggregated people movements or anticipating mobile blackspots and network congestion during emergencies — aren’t technically feasible (yet). But the platform has created a structure where feedback can continue, and where the tech can keep evolving alongside the community.

A few ingredients were critical:

And above all: follow through. The community saw that what they said mattered — not just in theory, but in what actually got built.

The Dargo platform is still in use — and still evolving. The community continues to feed in ideas, test new layers, and explore improvements like offline functionality for when communications infrastructure is down.

As we consider how this model could support other communities, we’re moving carefully. Scaling doesn’t mean replicating the tool as-is. It means holding onto what made it work — deep engagement, shared ownership and enough flexibility to meet communities where they are.

This pilot also challenged how we think about responsible innovation. It reminded us that building ethical tools isn’t enough. We also need to build the conditions that make ethical tools possible — shared language, flexible governance, and the time to get it right.

What happened in Dargo isn’t just a local success story. It’s a practical demonstration of how community knowledge and climate technology can work together — not in competition, but in collaboration.

If you’re developing technology for resilience, here are a few things to keep in mind:

And make sure that when you hand over the keys, that community has been driving all along.

Red Cross pays our respects to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander custodians of the country where we work, and to Elders, past, present and emerging.

Learn about our Reconciliation Action Plan and how we can all make reconciliation real.

This website may contain the images, voices or names of people who have passed away.

© Australian Red Cross 2026. ABN 50 169 561 394